The Man Who Refused to Spy

Legal Docket by CourtListener: United States v. Asgari (1:16-cr-00124)

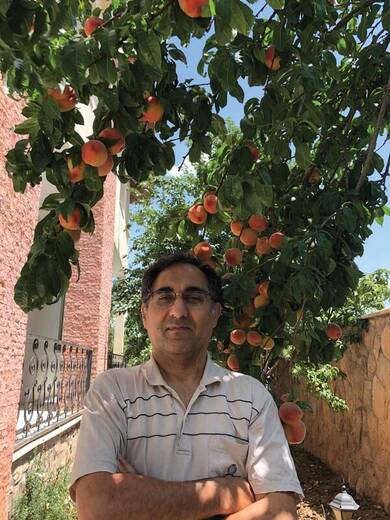

Professor Sirous Asgari Source: New Yorker

Professor Sirous Asgari Source: New Yorker

On September 14, 2020, the New Yorker published the story of Professor Sirous Asgari, an Iranian materials scientist.

F.B.I. tried to recruit Professor Asgari as an informant. When he balked, the payback was brutal.

According to the report, the FBI began to target Professor Asgari in 2012 and obtained a search warrant for a wiretap, claiming probable cause to believe that Asgari was violating U.S. sanctions, giving FBI access to e-mails in Asgari’s Gmail account from as far back as 2011. "Someone in the F.B.I. may have truly believed that Asgari was funnelling industrial secrets to Iran. But the way the agency conducted its investigation suggested a fishing expedition—and an attempt to push Asgari into becoming an informant." Professor Asgari refused and returned to Iran in 2013 while his children who are American citizens stayed in the U.S.

When Professor Asgari returned to New York in 2017, he was greeted by a sealed indictment, charging him for trade secret theft, wire fraud, and visa fraud. "Each time, he refused to enter a guilty plea or to become an informant. The F.B.I. grew increasingly frustrated and angry with him—and he began to understand that rebuffing the Bureau’s overtures would cost him. The government was prepared to prosecute him, even with a threadbare indictment."

"Before the proceedings began, Asgari and his attorneys obtained copies of the 2013 and 2015 search warrants, and they felt at once stunned and vindicated. As they saw it, the F.B.I. had secured the wiretap warrants based on little more than Asgari’s nationality."

"The trial began on November 12, 2019. Professor Asgari had allegedly stolen trade secrets, but from a company that had suffered no apparent injury, and to nobody’s profit. The supposed trade secrets had all been published in patents and scientific journals... Such was the heart of the prosecution: a recipe Asgari never asked for and never used, a faulty data set, and a student’s amateurish grant proposal that went nowhere. The visa and wire-fraud counts were similarly flimsy. The defense filed a motion to dismiss all charges." The presiding judge James Gwin accepted the motion.

No sooner had Judge Gwin departed the courtroom than a marshal seated in the gallery approached the defense table to haul Asgari into custody by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). "The turn of events was stunning. Asgari had just been acquitted in a fair trial before a federal judge, but would end the day in prison. By all appearances, the government was acting out of vindictiveness."

"The day Asgari was cleared of all charges, he began a seven-month descent down a spiral of squalor, into a vast carceral system beyond the reach of the U.S. judiciary. Within the realm of ICE, there would be no public documents, no legal hearings. His federal defenders could not help him." He was infected by the coronavirus while in detention, and was fortunate to recover while one of his guards died of COVID-19.

He believed that his time in detention had given him a more complete picture of American society than most citizens possessed. "I have friends in low places," he often told me, with a chuckle. He’d spent two years in the federal court system and five months in the clutches of ICE, all because the F.B.I. had tried and failed to recruit him, and because his visa—if it really was a visa—had never been stamped. He felt sympathy for the desperation that had led the American inmates to drugs and crime. “They’re boys from the middle of nowhere,” Asgari told New Yorker.

Asgari concluded that he was a victim of American law enforced by Soviet-style procedures.

“I appeared as an Iranian in front of an American judge,” he reflected. “This American judge ruled against an F.B.I. agent in my favor. I was privileged to witness the way he handled the trial, from jury selection to the end, the way he advocated impartiality and fairness. I believe these are global values that should be respected by all governments, including my own.” He added, “My attorneys, who put their heart into this thing—they were employees of the same government that was on the other side of this case.”

In early June 2020, after seven months in ICE custody, Professor Asgari finally returned home to Iran.

F.B.I. tried to recruit Professor Asgari as an informant. When he balked, the payback was brutal.

According to the report, the FBI began to target Professor Asgari in 2012 and obtained a search warrant for a wiretap, claiming probable cause to believe that Asgari was violating U.S. sanctions, giving FBI access to e-mails in Asgari’s Gmail account from as far back as 2011. "Someone in the F.B.I. may have truly believed that Asgari was funnelling industrial secrets to Iran. But the way the agency conducted its investigation suggested a fishing expedition—and an attempt to push Asgari into becoming an informant." Professor Asgari refused and returned to Iran in 2013 while his children who are American citizens stayed in the U.S.

When Professor Asgari returned to New York in 2017, he was greeted by a sealed indictment, charging him for trade secret theft, wire fraud, and visa fraud. "Each time, he refused to enter a guilty plea or to become an informant. The F.B.I. grew increasingly frustrated and angry with him—and he began to understand that rebuffing the Bureau’s overtures would cost him. The government was prepared to prosecute him, even with a threadbare indictment."

"Before the proceedings began, Asgari and his attorneys obtained copies of the 2013 and 2015 search warrants, and they felt at once stunned and vindicated. As they saw it, the F.B.I. had secured the wiretap warrants based on little more than Asgari’s nationality."

"The trial began on November 12, 2019. Professor Asgari had allegedly stolen trade secrets, but from a company that had suffered no apparent injury, and to nobody’s profit. The supposed trade secrets had all been published in patents and scientific journals... Such was the heart of the prosecution: a recipe Asgari never asked for and never used, a faulty data set, and a student’s amateurish grant proposal that went nowhere. The visa and wire-fraud counts were similarly flimsy. The defense filed a motion to dismiss all charges." The presiding judge James Gwin accepted the motion.

No sooner had Judge Gwin departed the courtroom than a marshal seated in the gallery approached the defense table to haul Asgari into custody by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). "The turn of events was stunning. Asgari had just been acquitted in a fair trial before a federal judge, but would end the day in prison. By all appearances, the government was acting out of vindictiveness."

"The day Asgari was cleared of all charges, he began a seven-month descent down a spiral of squalor, into a vast carceral system beyond the reach of the U.S. judiciary. Within the realm of ICE, there would be no public documents, no legal hearings. His federal defenders could not help him." He was infected by the coronavirus while in detention, and was fortunate to recover while one of his guards died of COVID-19.

He believed that his time in detention had given him a more complete picture of American society than most citizens possessed. "I have friends in low places," he often told me, with a chuckle. He’d spent two years in the federal court system and five months in the clutches of ICE, all because the F.B.I. had tried and failed to recruit him, and because his visa—if it really was a visa—had never been stamped. He felt sympathy for the desperation that had led the American inmates to drugs and crime. “They’re boys from the middle of nowhere,” Asgari told New Yorker.

Asgari concluded that he was a victim of American law enforced by Soviet-style procedures.

“I appeared as an Iranian in front of an American judge,” he reflected. “This American judge ruled against an F.B.I. agent in my favor. I was privileged to witness the way he handled the trial, from jury selection to the end, the way he advocated impartiality and fairness. I believe these are global values that should be respected by all governments, including my own.” He added, “My attorneys, who put their heart into this thing—they were employees of the same government that was on the other side of this case.”

In early June 2020, after seven months in ICE custody, Professor Asgari finally returned home to Iran.

Additional Links and References

2020/10/05 APA Justice: October 2020 Meeting Summary

2020/09/14 New Yorker: The Man Who Refused to Spy

2020/09/14 New Yorker: The Man Who Refused to Spy