|

English | 中文

| ||||||||||||

| |||||||||

|

Introduction

A new wave of Chinese immigration is now arriving in America, different than prior waves. The new arrivals embrace what their predecessors forswore. From the model minority myth to the perpetual foreigner syndrome, the new Chinese diaspora is staking out a conception of Chinese American identity that is Sinocentric and empowered. This article, based on the opening keynote speech of the CHSA Conference, analyzes how this new wave is unlike the Chinese American community that preceded it. The work is descriptive, not normative; that is, the point is to be objective, not to pass judgment on either newcomers or those whose families came earlier. It is perforce general, with the risk of error that arises from any report about groups in the aggregate. None of these changes is unusual. Jewish migration to the United States included a Sephardic wave; an Ashkenazi and German, Yiddish-speaking wave; and a later Eastern European wave. Among them were those who were assimilated to European high culture and educated, who were relatively privileged, and there were mutual apprehensions among these waves. The intellectual discourse among African Americans included the “debate” between Booker T. Washington, who suggested Blacks “cast down your bucket where you are,” and W. E. B. DuBois, who urged “the Talented Tenth” to insist on equality; not to mention plans such as for repatriation to Liberia or colonization as promoted by Marcus Garvey. That was followed by the conventional if not clichéd dichotomy between Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. Likewise, the Chinese diaspora in the United States has included everyone from Sun Yat-Sen, founder of modern China, and Soong Mei-Ling, better known as Madame Chiang Kai-Shek, who secured U.S. support for China during World War II, to Ai Wei Wei, the avant-garde artist. Sun spent formative years in Hawaii with his elder brother, in the 1880s; Madame Chiang attended college in Georgia and retired in the States; and Ai began attracting acclaim for his art in New York City a century later. |

|

Two Earlier Waves of Chinese Immigrants

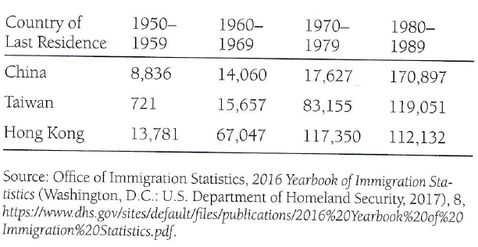

To understand the new wave, it is necessary to recall the two earlier waves. There are various means of classifying Chinese immigrants. For the sake of simplicity, only two categories are used here: those who came prior to the Magnuson Act, also known as the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act of 1943, and those who came afterward, until the advent of the new wave. The McCarran-Walter Act of 1952 could be used as the dividing line, but the earlier date groups together the Chinese who were resident in the United States during World War II, who landed during the hostilities, or who came during the immediate postwar period, with the later entrants, which seems in sociological terms more appropriate. The classes are demarcated by U.S. immigration policy, but they also correlate roughly to Chinese historical periods. These two groups are quite different from one another. It begins with their roots. The earliest Chinese immigrants were virtually all men from Canton or the Pearl River Delta, southern coastal areas that used the Cantonese language. There were exceptions, including a few well-to-do merchants or sons of families that could be described as mercantile, but these individuals were rare, and women even more so. They worked on the transcontinental railroad, laying the Western tracks from California to Promontory Point, Utah. Some also were recruited unwittingly as strikebreakers in Eastern factories, others to the Deep South during Reconstruction, in a scheme to replace freed slaves. A few families sailed in junks to Monterey, California. The next Chinese immigrants had a broader range of geographical origins, and they included significantly more who used the Mandarin language. Although the persons who were diplomats or from other elite backgrounds remained uncommon, they had become less scarce in absolute terms and more significant in proportional terms (because immigration exclusion ensured extremely low overall numbers). From 1949, for two generations (forty years), the bulk of Chinese immigration started not from mainland China, due to restrictions on emigration, but from Taiwan and Hong Kong, as well as other places where Chinese had settled, such as the Philippines, Vietnam, or Malaysia, or even in a few instances locations such as within the Caribbean—of course it all commenced at some point on mainland China, but it passed through these places, with pauses of even longer than a single generation. The few Chinese from the mainland during the Cold War era would have been extraordinary—refugees or defectors. However, these two earlier groups together can be distinguished from the current flow by the environment. They came at a time of open, harsh, unabashed discrimination against Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans. These were de jure measures, meaning they were formal laws (whether federal or state, statutory or decisional), that disadvantaged persons of Chinese ancestry. They included the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which prohibited further migration subject to limited quotas (and circumvented by “paper sons”); the subsequent Geary Act, which required Chinese who had come legally to carry papers at all times, to avoid summary deportation; and limits on land ownership, intermarriage, and professional licensure. They also included attempts—defeated in the courts—to enforce neutral regulations in a racial manner, such as by denying almost all Chinese applicants the requisite permits to operate laundries in San Francisco while granting almost all non-Chinese competitors the same privilege. The ongoing existence of Chinese Americans was endangered because they were barred from naturalizing on a racial basis (though some managed to do so under the standard of “free white persons”). The United States opposed, unsuccessfully, the recognition of citizenship by birthright. In the “separate but equal” era between the 1896 decision of Plessy v. Ferguson and the 1954 decision of Brown v. Board of Education, Asians—specifically Chinese—were deemed no different than African Americans, insofar as segregation could be practiced (though enforcement was not uniform). The bigotry was comprehensive. Prior to the 1964 Civil Rights Act, barring private parties from the practices, it was customary to refuse employment, housing, and public accommodations to even Chinese Americans who were bona fide citizens. Nor was the intolerance limited to xenophobia or a principled distinction between citizens and foreigners, because it extended to Chinese Americans but not European immigrants. Even prior to the current flow, these two groups of Chinese Americans were discrete. The earliest Chinese immigrants were laborers who faced occupational segmentation, which concentrated them in the crews building the railroad, laundries, restaurants, owners of small businesses serving ethnic clientele (e.g., insurance brokers), and, in the Deep South, proprietors of grocery stores for Black or impoverished White patrons. The next Chinese immigrants were professionals, including students on scholarship who stayed after completion of their degrees, and others who could qualify on the basis of skills that were needed within the domestic economy, such as health care service providers. The former formed an urban, Cantonese-speaking community; the latter, by and large a suburban, Mandarin-speaking counterpart. While these communities had contact, they nonetheless were separated by multiple factors, including the founding of churches and language schools that functioned as centers of social life. A church that conducted worship in Cantonese would not appeal to a family that was not Christian, nor to a family that was Christian but was fluent in only Mandarin. A language school that had instruction in Mandarin would attract few families that wished to maintain Cantonese (these language schools had a further decision with political implications, whether to use the simplified ideograms developed on the mainland or the traditional characters still in use in Taiwan and Hong Kong). Despite their differences, these two groups converged toward shared traits. As they formed associations to advance equality, their civic engagement has depended on a set of strategies. That has been the case especially as Chinese Americans have joined others to become Asian Americans. The term itself was invented by scholar Yuji Ichioka in the late 1960s. The trends that made “Asian American” a reality emerged with the cultural revolutions of 1967, when the “Summer of Love” occurred in the San Francisco Bay Area, and 1968, when civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. and presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated. A Yellow Power Movement brought together Chinese Americans, Japanese Americans, and Filipino Americans, primarily students, emulating the Black Power Movement and participating in the Third World Strike. The activism was circumscribed by time (the late 1960s and early 1970s), geography (centering on California), and generation (young, native-born). Another round of protests occurred with the campaign of “Justice for Vincent Chin.” A Chinese American killed with a baseball bat in 1982 in Detroit, “the Motor City,” by White autoworkers who apparently blamed him for the success of Japanese imported cars, he became an iconic martyr after the murderers were each given three years of probation and a $3000 fine. That effort brought together multiple ethnicities, because of the “mistaken identity” twice over (Chinese for Japanese, American for foreign). Among the accomplishments of the movement was the creation of Asian American Studies as an academic discipline. The practitioners were self-consciously “of” the community. They sought to forge an identity through scholarship. Their research, and the accompanying advocacy, has had clear themes. They were pan–Asian American in a form of mutual defense. Both words in the artificial identity were important. They encouraged bridge building among Asian ethnicities in America, acknowledging that “Asian” was associated with the imperialism of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, a euphemism for Japanese imperial aggression. The Asian ancestors of Asian Americans may have hated one another, may even have fought total wars among themselves. These Asian Americans proclaimed that they were loyal Americans, however they may have felt about assimilation. They were not sojourners who were temporarily resident, or perpetual foreigners relegated to second-class status. During the Cold War, it was in the interests of Chinese Americans particularly to lay claim to a U.S. passport, to avoid suspicions when a “confession” program was under way to ferret out those whose ancestors included illegal immigrants. The government correspondingly had reason to refute the notion that the United States was racist to promote its image, in contrast to the Soviet Union, with nations that had populations who resembled the people of color in the States. Among the recurring concerns for “Asian Americanists,” as those in the field called themselves, was debunking the “model minority myth.” The image that Asian Americans were highly successful, overcoming prejudice without government intervention, in pointed comparison with African Americans and Latinos, was challenged as empirically false, for failing to take into account selective migration, educational attainment, multigeneration households, concentration of the demographic in higher-wage areas, and dissimilar stereotypes. A multitude of books, articles, and op-eds were produced to demonstrate either that Asian Americans were normal or that their achievements on average were attributable to factors other than some sort of ethnic superiority. These tenets are exemplified by the Organization of Chinese Americans. A nonprofit founded in 1973, OCA adopted bylaws that deliberately stayed away homeland politics by restraining themselves from expressing opinions on “politics of any foreign country.” They subsequently amended their name to the abbreviation “OCA” to indicate they aspired to represent all Asian Americans. They belong to the Washington, D.C.–based umbrella group, the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, founded by labor unions, Jewish, and African American organizations. The earlier Chinese American Citizens Alliance, which initially was constituted as the Native Sons of the Golden State (akin to the Whites-only Native Sons of the Golden West), similarly was, as indicated by both names, prideful about citizenship and native status. Japanese Americans were even more patriotic. The Japanese American Citizens League was criticized for acquiescing to the World War II internment. |

|

Conclusion

To the extent anyone is implicitly taken to task here, it is progressive Chinese American leaders who have failed to engage with newcomers. They ignore this growing population at their own peril. The assumption that Chinese Americans are homogeneous is wrong. Many Chinese Americans do not agree with a liberal ideology. Theirs is as authentic a version of the Chinese American experience. It may become the prevailing one. Or perhaps the project of uniting Chinese Americans, on the basis of ethnic affinities, is not possible in practical terms, regardless of whether it is imagined to be ideal. Chinese Americans, as Chinese Americans, may have much in common, yet they also exhibit the diversity that defines democracy. |